Constantine VII

| Constantine VII | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Byzantine Empire | |

|

|

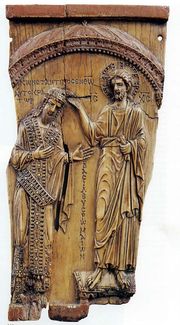

| Constantine and his mother Zoë. | |

| Reign | Co-emperor 908 – 945

Emperor January 27, 945 – November 9, 959 |

| Full name | Constantine Porphyrogenitus

(Born of the Purple Room) |

| Born | September 2, 905 |

| Birthplace | Constantinople |

| Died | November 9, 959 (aged 54) |

| Place of death | Constantinople |

| Predecessor | Alexander |

| Successor | Romanos II |

| Wife | Helena Lekapene |

| Offspring | Romanos II

Theodroa |

| Dynasty | Macedonian dynasty |

| Father | Leo VI |

| Mother | Zoe Karbonopsina |

Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos or Porphyrogenitus, "the Purple-born" (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Ζ΄ Πορφυρογέννητος, Kōnstantinos VII Porphyrogennētos), (September 2, 905 – November 9, 959) was the son of the Byzantine emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife Zoe Karbonopsina. He was also the nephew of the Emperor Alexander. He is famous for his four descriptive books, De Administrando Imperio, De Ceremoniis, De Thematibus and Vita Basilii.

His nickname alludes to the Purple Room of the imperial palace, decorated with the stone porphyry, where legitimate children of reigning emperors were normally born. Constantine was also born in this room, although his mother Zoe had not been married to Leo at that time. Nevertheless, the epithet allowed him to underline his position as the legitimized son, as opposed to all others who claimed the throne during his lifetime. Sons born to a reigning Emperor held precedence in the Byzantine line of ascension over elder sons not born "in the purple".

Contents |

Reign

Constantine was born at Constantinople, an illegitimate son born before an uncanonical fourth marriage. To help legitimize him, his mother gave birth to him in the Purple Room of the imperial palace, hence his nickname Porphyrogennetos. He was symbolically elevated to the throne as a two-year-old child by his father and uncle on May 15, 908. After the death of his uncle Alexander in 913 and the failure of the usurpation of Constantine Doukas, he succeeded to the throne at the age of seven, under the regency of the Patriarch Nicholas Mystikos.

His regent was presently forced to make peace with Tsar Simeon of Bulgaria, whom he reluctantly recognized as Bulgarian emperor. Because of this unpopular concession, Nicholas was driven out of the regency by Constantine's mother Zoe.

Zoe was no more successful with the Bulgarians, by whom her main supporter, the general Leo Phokas, was defeated in 917, and in 919 she was replaced by the admiral Romanos Lekapenos, who married his daughter Helena Lekapene to Constantine. Romanos used his position to advance to the ranks of basileopatōr in May 919, kaisar (Caesar) in September 920, and finally co-emperor in December of the same year. Thus, just short of reaching nominal majority, Constantine was again eclipsed by a senior emperor.

Constantine's youth had been a sad one for his unpleasant appearance, his taciturn nature and his relegation at the third level of succession behind Christopher Lekapenos, the eldest son of Romanos I Lekapenos. Nevertheless, he was a very intelligent young man with a large range of interests, and dedicated those years to study the court's ceremonial.

Romanos kept power for himself and maintained it until 944, when he was deposed by his sons, the co-emperors Stephen and Constantine. Romanos spent the last years of his life in exile on the Island of Prote as a monk and died on June 15, 948.[1] With the help of his wife, Constantine VII succeeded in removing his brothers-in-law and on January 27, 945, Constantine VII was once again sole emperor at the age of 39, after a life spent in the shadow. Several months later, Constantine VII crowned his own son Romanos II co-emperor. Having never exercised executive authority, Constantine remained primarily devoted to his scholarly pursuits and relegated his authority to bureaucrats and generals, as well as his energetic wife Helena Lekapene.

In 949 Constantine launched a new fleet of 100 ships (20 dromons, 64 chelandia, and 10 galleys) against the Arab corsairs hiding in Crete, but like his father's attempt to retake the island in 911, this attempt also failed. On the Eastern frontier things went better, even if with alternate success: in 949 the Byzantines conquered Germanicea, repeatedly defeated the enemy armies and in 952 crossed the upper Euphrates. But in 953 the Arab amir Sayf al-Daula retook Germanicea and entered the imperial territory. The land in the east was eventually recovered by Nikephoros Phokas, who conquered Hadath, in northern Syria, in 958, and by the Armenian general John Tzimiskes, who one year later captured Samosata, in northern Mesopotamia. An Arab fleet was also destroyed by Greek fire in 957. Constantine's efforts to retake themes lost to the Arabs were the first such efforts to have any real success.

Constantine had intense diplomatic relationships with foreign courts, including the caliph of Cordoba Abd ar-Rahman III and Otto I, King of Germany. In the autumn of 957 Constantine was visited by Olga, princess of the Kievan Rus'. The reasons for this voyage have never been clarified: in any case, she was baptised with the name Helena, and began to convert her people to Christianity.

Constantine VII died at Constantinople in November 959 and was succeeded by his son Romanos II. It was rumored that Constantine had been poisoned by his son or his daughter-in-law Theophano.

Literary and political activity

,_deathbed.jpg)

Constantine VII was renowned for his abilities as a writer and scholar. He wrote, or had commissioned, the works De cerimoniis aulae byzantinae ("On Ceremonies"), describing the kinds of court ceremonies also described later in a more negative light by Liutprand of Cremona; De Administrando Imperio ("On the Administration of the Empire"), giving advice on running the empire internally and also how to fight external enemies; and a history of the Empire covering events following the death of the chronographer Theophanes the Confessor in 817. Amongst his historical works was a history eulogising the reign and achievements of his grandfather, Basil I. These books are insightful and are of immense interest to the historian, sociologist and anthropologist as a most useful source of information about nations neighbouring with Byzantium. They also offer a fine insight into the Emperor himself.

In his book, A Short History of Byzantium, John Julius Norwich refers to Constantine VII as "The Scholar Emperor" (180). Norwich states, “He was, we are told, a passionate collector—not only of books and manuscripts but works of art of every kind; more remarkable still for a man of his class, he seems to have been an excellent painter. He was the most generous of patrons—to writers and scholars, artists and craftsmen. Finally, he was an excellent Emperor: a competent, conscientious and hard-working administrator and an inspired picker of men, whose appointments to military, naval, ecclesiastical, civil and academic posts were both imaginative and successful. He did much to develop higher education and took a special interest in the administration of justice (181). In 947, Constantine VII ordered the immediate restitution, without compensation, of all peasant lands, thus, by the end of [his] reign, the condition of the landed peasantry—which formed the foundation of the whole economic and military strength of the Empire—was better off than it had been for a century" (182–3).

Family

By his wife Helena Lekapene, the daughter of Emperor Romanos I, Constantine VII had several children, including:

- Leo, who died young.

- Romanos II.

- Zoe. Sent to a convent.

- Theodora, who married Emperor John I Tzimiskes.

- Agatha. Sent to a convent.

- Theophano, daughter in-law.

- Theophano. Sent to a convent.

- Anna. Sent to a convent.

Notes

References

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press.

- Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. London: Viking. ISBN 0679450882.

- Runciman, Steven (1990) [1929]. The Emperor Romanus Lecapenus and his Reign. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 0521357225.

- Toynbee, Arnold (1973). Constantine Porphyrogenitus and his world. Oxford. ISBN 019215253X.

External links

- Listing of Constantine VII and his family in "Medieval Lands"

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

- De administrando Imperio chapters 29–36 at the Internet Archive

|

Constantine VII

Macedonian Dynasty

Born: September 905 Died: 9 November 959 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alexander |

Byzantine Emperor 913–959 with Romanos I (920–944) Christopher Lekapenos (921–931) Stephen Lekapenos (924–945) Constantine Lekapenos (924–945) |

Succeeded by Romanos II |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||